Three Lessons From Week One

Search is all AI now, students want guidance, and my biggest surprise wasn't AI.

Everyone has a plan until they get punched in the mouth.

Mike Tyson

I wasn’t punched this week, far from it, but I did walk back into the classroom with some trepidation after a summer obsessing over AI and pedagogy. How would three months of rumination hold up against the reality of actual students? Had I diagnosed the problem accurately or misread it entirely? Four days in, my gut says my instincts were right. Students have jumped right back into AI; it’s the default. They have plenty of strong opinions but, crucially, seem willing to listen. Whether that openness turns into better habits is the test for 2025 - 2026. How can we get them to pause before outsourcing every question to an LLM? Here are my three takeaways from week one:

ChatGPT is the new Google

My older students had already cemented ChatGPT into their workflow by the end of last year, but now it’s bookmarked on every laptop. It’s the go-to fact-checker. Students who swore it off in the spring are using it openly. Meanwhile, Google has become ChatGPT inside a web-browser.

When I launched one lesson with a simple research task and the instruction, “use any tool you want,” half the class went straight to ChatGPT. Those that didn’t started with Google and toggled back and forth with GPT-5. But the goal wasn’t to see who was the fastest. I wanted them to realize how a deceptively simple prompt (“Who was the richest person in history?”) gets messy when an AI returns a confident answer. The real test was whether anyone would pause long enough to think about the question before dumping it into a chatbot.

The Importance of Questions

For a research question like this, before we even think about names, we need to pin down what’s being assumed - are we comparing a king’s control of a state treasury to the fortune of a private citizen? Would Augustus’s “wealth” count as his, or Rome’s? And how do you normalize metrics across centuries with incomparable prices, currencies, purchasing power, or share of global GDP? What’s the unit being used and how do you translate that into a modern equivalent? In other words, to actually answer this question, you have to ask a lot more. How many students do you think would pause to do that before simply pasting the query into an LLM?

And, let’s be clear, as I wrote earlier this summer, even if they use Google, Google search IS AI search. The AI Overview is merely a front-loaded LLM answer sitting on top of the results, and most treat it as the answer, not the starting line.

It’s time to stop pretending that “ban AI” is a coherent strategy. When Google’s AI Search Mode is a click away, and students usually stop at the overview, teaching AI literacy isn’t optional.

Almost everyone got “Mansa Musa,” the 14th-century ruler of Mali, as the consensus choice.1 When I asked how many had clicked a source or even opened the “Show more” dropdown, only a few raised their hands. ChatGPT’s replies were deeper, but usually came up with the same response. Students also took them at face value. Even when they acknowledged some ambiguity, there was little pushback, sourcing, or follow-up prompting by students.

On closer inspection, a few things were obvious. Outputs aren’t identical even with the same prompt. Some answers acknowledged how hard it is to compare wealth across eras while others listed contenders with bracketed “estimates” of net worth absent any context unless you checked the citation, assuming there was one.

The most instructive moment came when one summary crowned Mansa Musa the winner with a “comparative net worth” of $400 billion while, in the next paragraph, mentioning Augustus and Emperor Shenzong with estimates in the trillions, yet not calling either the richest.

What happened here? If you didn’t read carefully and critically, you’d miss the contradiction.

The Danger of AI Overviews

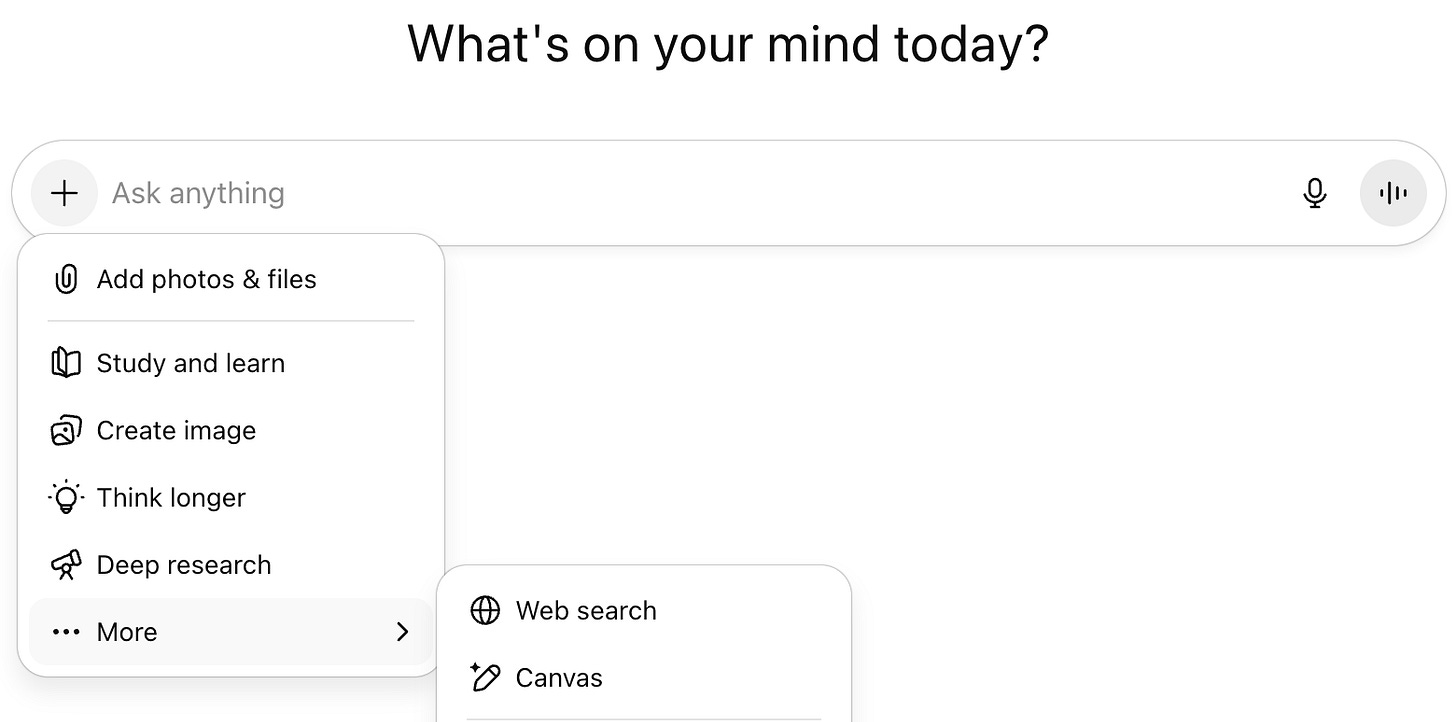

This raises the only question that matters - where is this information actually coming from and how are answers determined? AI Overviews remove the old friction of clicking through and reading by substituting algorithmic synthesis over human judgment. One upside is that Google’s overview usually does provide links, but they’re useful only if you actually read them. ChatGPT often won’t even give you those links unless you ask. You can hit the plus symbol and choose web search beforehand, but how many people do you think actually do that given that it’s buried under two drop down menus?

Here is where Mike Caulfield’s SIFT method,2 which I learned about this summer, comes in so handy. If students are going to use AI to search - and they are - then show them how to use it iteratively with challenging prompts: “Show your sources,” “Argue the other side,” “How did you reach that conclusion?” Then you might have something worth reporting.

Students Actually Want to Talk About AI — And Learn Its Limits

The richest-person research question didn’t just expose the flaws in the models. It opened a real conversation. Once we watched in real time how confident answers unraveled under scrutiny, we started asking smarter questions: How do you press AI to ask for sources? What’s hallucination versus interpretation? Why are the same prompts giving different answers and how come they sound so confident when they do?

This activity had nothing to do with cheating. It was about trying to understand. That’s the hook. If AI-infused search is now the default - and it is - then our job is to teach students how to interrogate it. Not to bring ChatGPT into the classroom, but to acknowledge that the most used browser in the world now has an AI model inside it. AI literacy starts with reality.

Writing Is Still Sacred

In a different class, I started with 50 minutes of handwritten, in-class freewriting. I scanned, transcribed, ran each piece through a custom GPT to identify patterns, then added my own feedback on top. This wasn’t AI grading. It was a diagnostic exercise. Now each student has a baseline writing sample and a strengths/growth document they can be used to evaluate future work.

What I found in these early entries was familiar to anyone who teaches high school. Wonderful, quirky, uniquely human observations and personal experiences that AI can’t fill. We need assignments that matter with real feedback and time to revise.

Here’s the contract I’m making to myself this year: if I want real thinking, I have to ask for real writing by giving prompts that require depth.

I was especially encouraged by the work from my seniors, who kicked off the year with a writing assignment responding to an essay that provocatively argued we should “avoid the news.” The questions were serious, the topic relevant, and the writing that came back was passionate, personal, and critically engaged. When we ask students real questions and give them space to respond with their own perspective, they don’t want to cheat. They want to be heard.

That contract only works if the assignment is worth the time. With large class sizes and heavier teaching loads, teachers can’t conference every single paper. That’s why we need deeper writing tasks. Low stakes reading comprehension questions to be done outside the classroom are just not as useful given the ability of AI to complete them.

Final Thoughts: Ban Distraction, Teach Judgment

AI wasn’t the headline in our building this week. The biggest shift was a school wide, bell to bell cell phone ban. No scrolling between classes, no headphones in the hallways, and no phones anywhere on campus.

Students aren’t thrilled (publicly), but they’re adapting. The atmosphere changed overnight: more conversation, eye contact, and presence. It’s only been a week, but if this holds, it might be the most radical cultural shift we’ve seen in years.

That’s the line I’m trying to draw. Phones are distractions. AI is a decision. One can be managed with policy. The other requires teaching.

Phones disappear so students can be present with each other. But AI will show up wherever students write, search, or brainstorm wherever they are. Unless schools shut down wifi access, the only real choice is whether we teach them how to use it right or let them continue to figure it out on their own.

AI isn’t a device. It’s a system. I’d rather confront it with them than pretend it isn’t shaping the way they learn.

That was the bet I made this summer. I may eventually get punched in the mouth, and I realize the year has just begun, but I still like my odds.

In case you were wondering, Elon Musk doesn’t typically get mentioned, but you can try it yourself.

SIFT stands for: Stop (name what you’re actually asking), Investigate the source (who’s behind the claim), Find better coverage (quickly compare laterally across other sites or sources), and Trace the claim back to its original context if you can find it. Doing this for 30 seconds can yield a treasure trove of useful counter-information and lead to important questions.

Demonstrates some very thoughtful teaching! Maybe the best we can all hope for is for writers and researchers to be more critical of what they’re getting from Google and other AI programs

I'm always wonderfully challenged to broaden my thinking when I read your work and this post was no exception. Thanks for starting off the year with your students with such thoughtful lessons.

However, there was one thing that I've been thinking about a great deal and one of your last notions in this post brought it home. It was the section on dealing with "Distractions". How often do we question the notion that what the teacher has decided is important for students really IS important and that anything (phones, peers, etc) that draw students away from what the teacher has decided is important is, by definition, a distraction. What if our carefully planned instruction is actually the distraction in the student's day? We seem to display very little faith in our students' evolving maturity when we refuse to give them the opportunity to pursue what they may be interested in. We've systematically burned the curiosity out of them to the point where they don't even bother to wonder deeply anymore. Their natural curiosity is no longer a distraction in our classrooms--sadly. I have already seen enough of you in your writing to sense that you are truly a wonderful teacher and I have no doubt that whether a student was interested in entrepreneurship, economics, history, robotics, or anything else you could help them deepen their understanding and excitement while weaving in and encouraging them to explore the topic through literature or mathematics or biology. By helping them weave their own world together with strands from every discipline, we help them focus and understand that everything is an opportunity for learning.