My AI-Aware Strategy for the Year Ahead

Where I’ll Use AI in Class, Where I Won’t, and Why

Hundreds of hours spent reading, experimenting with, and writing about AI have taught me one thing: no one has a satisfying answer for how schools should respond. The issue is so new, so divisive, and so tangled in unspoken assumptions about learning and technology that even civil conversations can quickly devolve into ideological binaries. I’ve been wrestling with the implications of AI in schools for nearly three years - as a parent, a citizen, but mostly as a thirty-year classroom teacher. In that time, it’s become undeniable: enough high school and college students have folded AI into their daily routine to seriously challenge the traditional model of education. For decades, we’ve assigned substantial graded written work to be completed outside of class. Now, AI can do much of it, and the temptation is only increasing. The question for educators everywhere is to think through what teaching and learning look like against the backdrop of a world of abundant AI.

Three observations stand out: first, 2025–26 will be the year schools can no longer ignore how generative AI is reshaping the traditional contract of schooling; second, students are beginning to outpace faculty in adoption and everyday use of AI; third, teachers must understand these tools, if only to speak about them credibly with their students.

From that third point comes an even more contentious question: if teachers must understand AI - what it is, how it works, and what it can do - should they also be deploying it in class? And if so, when, and for what purpose?

There’s one more “truth” in the AI conversation that cannot be overstated. A handful of tech companies are spending staggering sums to accelerate AI capabilities as fast as possible. They control the release schedule and the narrative.1 Tech billionaires make sweeping, sometimes apocalyptic claims, and the rest of us scramble to make sense of them. It’s within this climate that teachers are expected to “solve” the AI dilemma.

My AI Approach for 2025 - 2026

What I am currently thinking through - and what I suspect most teachers are still grappling with - is whether, how, and under what circumstances AI belongs in their classrooms. We can’t control how students use it outside of school. My focus is on the work we assign and assess under our own supervision, and how, if at all, AI should have a place in that limited and valuable time together.

First Principles

Your class is not about AI. It’s about student learning outcomes.

If there’s a gift in the so-called AI “crisis,” it’s that it forces teachers to revisit first principles in the context of our courses, disciplines, and students. Every educator should start the school year asking themselves:

Three Key Questions

What do we want our students to know?

What do we want them to be able to do?

How will we help them get there?

None of these questions has anything to do with AI. Only after those are answered clearly can we even begin to consider any AI-specific questions, such as:

Is content knowledge less valuable when any facts and explanations can be summoned with a single prompt?

Do we have an obligation to prepare students for a world and workplace of abundant AI? If so, whose job is it?

What, specifically, about AI should be taught, and when?

Should we be redesigning classroom practice around AI’s presence? How is this implemented, measured, and evaluated?

My own guiding question when deciding whether to introduce AI in class is more direct: where might AI help, and where will it likely hinder learning? Despite the loudest voices in the media or online comments, the answers aren’t clear or obvious. It changes with age level, discipline, the purpose of the task, and how AI is actually used.

Why I Lean Toward Caution

Among those advocating for AI in classrooms, few get specific about what that looks like up close. Unsurprisingly, a large group of teachers intend to keep AI out of their teaching entirely. Some reject it outright but many do so because they haven’t found a compelling reason or clear use case. That’s an understandable default, and in many ways, the easiest to defend.

The bigger challenge is for those being nudged or pushed into AI use. Some districts and schools are giving explicit mandates. Many teachers will be surprised to learn that, over the summer, AI features were quietly embedded into existing platforms like Canvas or Google Classroom. Newly implemented academic integrity policies are still untested, there are few concrete successful examples of AI integration, and little to no research on best practices. This puts teachers - especially those whose experience with AI is shaky at best - in a precarious position.

That uncertainty continues to inform my own caution even as I’ve found using AI immensely helpful in my own work. With students, we have no solid data as to whether AI helps or harms learning, and the little we do have, especially in writing instruction, suggests it may be devastating to their development. More practically, I’m not yet convinced most high school students have the skills or self-discipline to avoid using AI in ways that short-circuit their own growth. Until we close those gaps, a measured, “wait and see” approach may still be the most prudent.

Nevertheless, I have had success with some specific lessons where I used AI in class. I will continue to investigate where AI might be valuable, especially in cases where I feel confident that demonstrating or allowing these tools will do more good than harm.

My Plan in Practice: Guiding Principles

I teach four different humanities classes which are all reading- and writing-intensive. For over two decades, I’ve been redesigning my curriculum to emphasize oral presentations, simulations, and alternative assessments alongside traditional essays and written work. That foundation makes it easier to adapt to AI without overhauling my entire pedagogy. My approach for this year rests on four principles:

1. Remove the temptation to use AI for assessed written work as much as possible.

Most major written assignments will be completed in class, either in marble composition books, or through lockdown browser. This eliminates the constant worry about whether a paper was AI-generated and keeps the focus on authentic expression. And for those writing tasks done outside of class, they will either be lower stakes or designed to be AI-resistant - think class discussion logs, in-class presentation scripts, or simulation responses where AI off-loading would be of limited assistance. More rarely, I may explicitly permit AI for a very specific purpose. In those cases, assignments will contain explicit instructions and requirements for how AI is to be used and require documentation and a reflection.

2. Keep an open mind for student use of AI for ungraded, outside-of-class work.

Given that we can’t control or reliably detect how students use AI in their daily study habits or preparation, I have no intention of policing it. If they choose to use AI to organize notes, generate study guides, create practice questions, or clarify a topic they didn’t fully grasp in class, I’m generally fine with that. I won’t actively encourage it, but I’m not going to scold them. These uses aren’t graded and, for students who’ve already adopted them, they may be helping. If this approach doesn’t work, I’ll revisit it.

3. Use AI intentionally where it may enhance learning and/or to illustrate its strengths and limitations.

When AI appears in my classroom, it’s there for a reason. I’ve already developed several lessons that successfully demonstrate ways in which AI can be useful. Across classes, I’ve used it methodically - to unpack a 16th century primary source after we’ve examined it ourselves, to audit a research plan, or to illustrate argumentation structure. Framing AI as one tool among many keeps the focus on judgment and learning rather than the novelty of the technology

4. Find space to talk about AI - with students and the adults around them.

I’m transparent with students about my own AI experiments. I’ve explained what’s worked, what hasn’t, and why I’m cautious. Many students share the same concerns adults do about AI over-reliance, especially in writing. On-going, open dialogue throughout the year will help them think critically about their own choices. It’s also likely that the AI news cycle will provide opportunities to talk about broader societal issues, including reports of job disruption as well as harder philosophical questions such as the value of “human” work in a future of powerful AI. Teenagers grasp those stakes more acutely given their lives and careers are ahead of them. Surfacing these issues in conversations with colleagues, administrators, and parents helps take the temperature of the community and align expectations. The goal isn’t consensus so much as clarity about how people are experiencing AI right now.

How That Looks in My Four Courses

10th Grade American History

With my sophomores, AI use is minimal. I’ve experimented with some things over the past two years, especially with AI’s multi-modal abilities and demonstrations of how AI can be used in the research process. I’ve also demonstrated AI-generated responses to assignments so students can analyze its strengths, weaknesses, and blind spots. The biggest change this year is I’ll move almost all graded writing to be done in class. The goal remains to build foundational skills and emphasize meaningful assignments in which students are personally invested. These can be debate speeches or simulation scenarios rather than simply essays or DBQ’s. AI’s capabilities will be acknowledged, not featured.

Government & Politics Elective (Juniors and Seniors)

AI use is limited but targeted. Students might use it for specific assignments such as preliminary research, helping break down complex Supreme Court cases, or acting as a second set of “ears” during an in-class foreign policy debate. I have several assignments where AI was effective, but the overwhelming majority of class time goes to discussion, in-class responses, mini-lectures, group work, oral presentations, debates, and simulations. In-class writing will be the norm, though I may occasionally model AI-generated feedback on drafts.

Independent Research in History (Advanced Elective)

This has been my AI “sandbox.” Over the past two years, students have used AI for research, brainstorming, outlining, and draft feedback. We’ve tried use cases that helped, such as generating alternative research paths, and others that fell flat. The goal is experimentation and discernment: knowing when AI is a useful tool and when it gets in the way. I spent part of the summer developing an AI-Aware Historical Research Framework for the course. Alongside traditional methods, I will now demonstrate Deep Research and Deep Search workflows and how to evaluate their output using Mike Caulfiled’s SIFT method. For advanced high school students learning research techniques, this is appropriate preparation; AI-assisted research is likely to become the norm. I want students ready for that world.

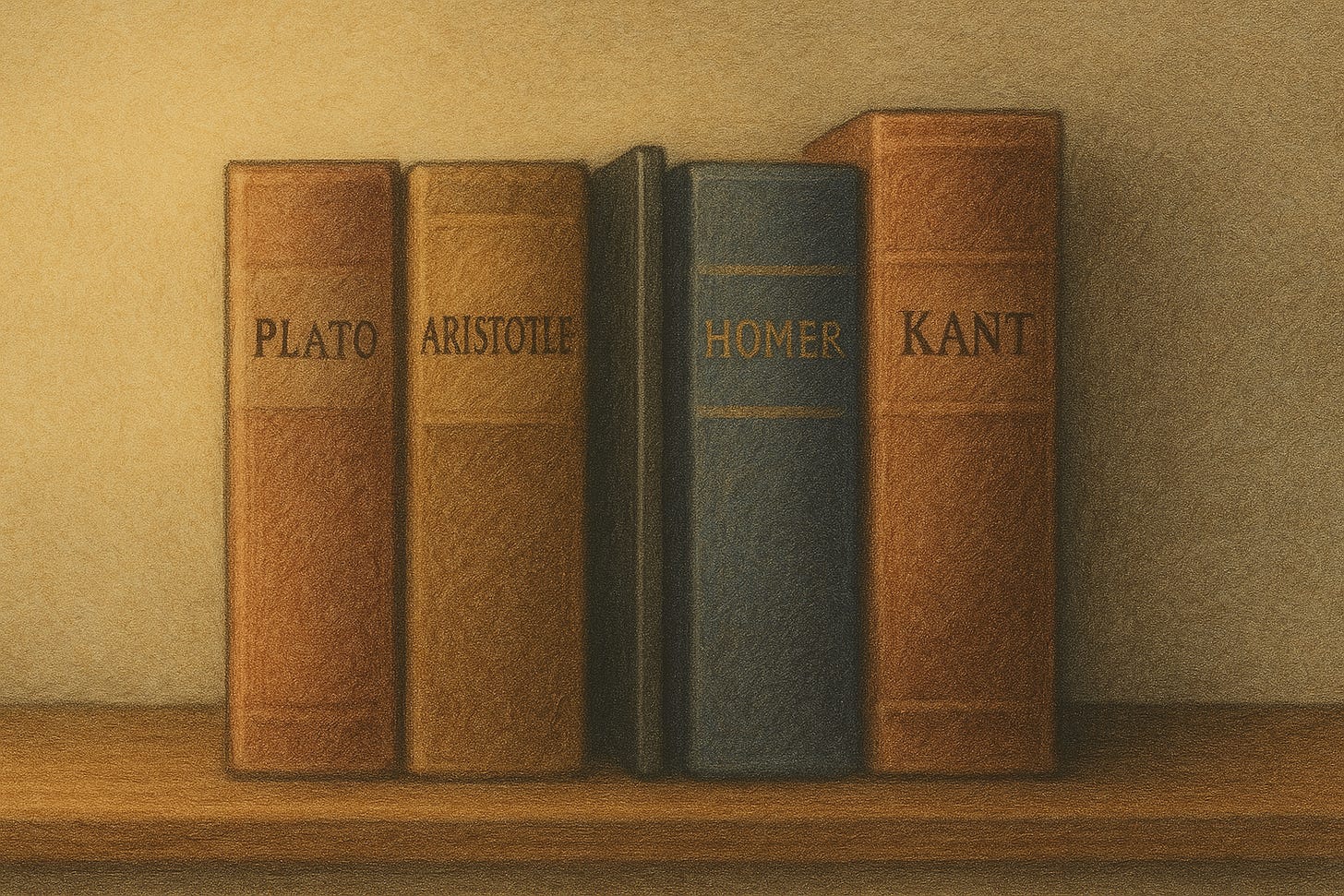

Great Books Seminar

Student AI use plays no role. The one successful application of AI in this class is when I used a custom GPT to generate ethical dilemmas for students to analyze through the lenses of different philosophical frameworks. Beyond that, the course focuses on slow reading, discussion, and close textual analysis where I want the emphasis purely on human interpretation and interaction.

Different classes call for different strategies. These examples show where I think AI fits and where it doesn’t. Reasonable people will choose differently. What matters now is trial and error and honest feedback so we learn where AI actually helps learning and where it harms it.

What I Won’t Do

Put AI at the center of my classroom.

Generative AI will keep dominating education headlines, and its long-term impact may be profound. But we don’t have the data or evidence to justify wholesale adoption. Too much is still unknown, and the risks compound when AI is implemented by teachers who don’t fully understand the tools or their limits. AI-Aware does not mean AI centered. I may occasionally feature or demonstrate AI, but the overwhelming majority of class time will be AI-free and focused on reading, writing, skill-building, and critical thinking.

Punish or police students for AI use outside class when it doesn’t clearly violate academic integrity.

I’ll err on the side of the student in gray areas, especially for first offenses. Repeated, clear-cut cases are different, but if most graded work happens in class, those should be rare. I won’t play cat-and-mouse trying to “catch” AI use. That energy is better spent building trust and helping students learn.

Revisit, Review, and Revise

None of these decisions are final. I reserve the right to change tactics mid-year based on real-time feedback and student discussions. Meanwhile, AI will continue to develop, and companies will keep releasing new models, with new benchmarks, and new capabilities. We’ll adjust again if and when breakthroughs warrant it. For now, teachers have enough to worry about.

In many ways, I’ve come full circle. My 2025–2026 approach is not significantly different from the past two years. My job is to adapt with care and maintain my focus where it matters most: the thinking, skills, and habits students need in a world with or without artificial intelligence. Whether they discover a better way to prompt, realize AI’s not the tool for them, or simply think more deeply about their own process, the most important goal is that they understand their own learning. How and whether AI has any meaningful and useful place in their education is ultimately going to be up to them.

Just look at the recent release of GPT-5 and the outpouring of coverage. Dozens of storylines with one major throughline - hundreds of millions of users at the mercy of a handful of decision makers.

Really appreciate the thoughtfulness and transparency of this post. As a parent, one thing I'd like to see is students allowed to officially use AI in some group projects so long as they officially give it a role and document how they used it. I described the concept here: https://open.substack.com/pub/mikewhitaker1/p/how-to-start-changing-the-ai-dynamics?r=mld5&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=false

'Your class is not about AI. It’s about student learning outcomes.' - spot on again, Stephen!

Reminds me of the excellent book 'Will it make the boat go faster?' about how the British rowing 8 went from consistent defeat to Olympic gold medal in Sydney 2000 by focusing rigidly on that question. If something made the boat go faster, they did it. If it didn't, they ignored it.

As educators, we might ask, 'Will it help my students learn?'

Of course, like the rowing 8, we don't know the answers yet so we have to experiment strategically and analyse the results with healthy scepticism.

But it certainly helps to focus on a simple question