What About the Students Who Don’t Cheat?

Inside the Quiet Divide AI Is Creating in the Classroom

While the AI-in-education debate remains fixated on ‘cheating,’ it often ignores the students who deliberately opt out. These students deserve more of our attention. Data from the Chronicle of Higher Education shows that 15–25% of students across several studies believe AI should not be used in education or refuse to use it themselves. In a recent post, I wrote that AI-proofing is a myth. This one looks at the collateral damage: students still trying to learn inside a system being exploited by cheaters. Many understandably resent the fact that their classmates are skating by with little effort. Some are suspected of dishonesty themselves. How long before they start to give in?

The Students No One Talks About

The cheating narrative dominates the coverage of AI in education. But many students have either rejected AI entirely or are using it in ways that don’t match the media’s worst-case examples. Unfortunately, the available data doesn’t clarify whether that 15–25% who “refuse” AI are rejecting all forms of it or just avoiding it to cheat.

That distinction matters. Students don’t all share the same understanding of what counts as cheating. Yet most commentators ignore that nuance and zero in on the most blatant cases, treating them as representative of the whole.

Juliana’s story is a perfect example that complicates the binary. She uses AI, but sparingly - to organize, to clarify, to get unstuck. Not to write her work. When students like her are lumped in with cheaters, we lose sight of the real questions. What counts as acceptable use? Who decides?

Juliana Fiumidinisi, a rising sophomore at Fairfield University, is a fan of AI as a study aid. It has helped her outline and organize papers, and served as a math tutor, breaking down problems step by step.

But she feels that many people in her generation lack self control and turn to technology for instant gratification. She recalled studying hard for a psychology test, taking handwritten notes, making flashcards, and doing everything “the old way,” she said. “I didn’t use AI at all because I really wanted to know the content.”

“Then I went to take the test, and it was an open browser, and people were literally just copying and pasting the questions from the test into ChatGPT,” she said. “I was very upset, because I spent a lot of time studying. It took hours out of my week to study.”

“So that was a really frustrating moment for me.”

McMurtrie, Beth. “AI to the Rescue.” The Chronicle of Higher Education, 20 June 2025 (emphasis added)

Her frustration reveals what many honest students are up against. They’re doing the work while watching others shortcut the system and get away with it.

Given her acknowledgment of her own usage, maybe Juliana isn’t part of the 15–25% who say they’ve “refused” AI. But should she be grouped with the students who are clearly cheating? Her case raises a deeper issue: what do students actually mean when they say they’re not using AI?

The data doesn’t tell us whether they’re rejecting AI entirely or just what they define as cheating. Do teachers who have “banned” AI entirely really see no difference in the way Juliana uses AI versus her classmates?

Juliana’s case illustrates the complexity of how students actually use AI on campus.

How Long Can Resistance Last?

The more cheating goes unchecked, the harder it becomes for honest students to keep up.

When classmates are breezing through their coursework by relying on AI, where does that leave the students doing it for real? Imagine studying hard for a test, earning a B+, and knowing that others who barely prepared got A’s by blatantly cutting and pasting during the test.

It’s not hard to see why some will eventually give in. AI becomes the only way to stay competitive. I’ve openly heard students making this very point.

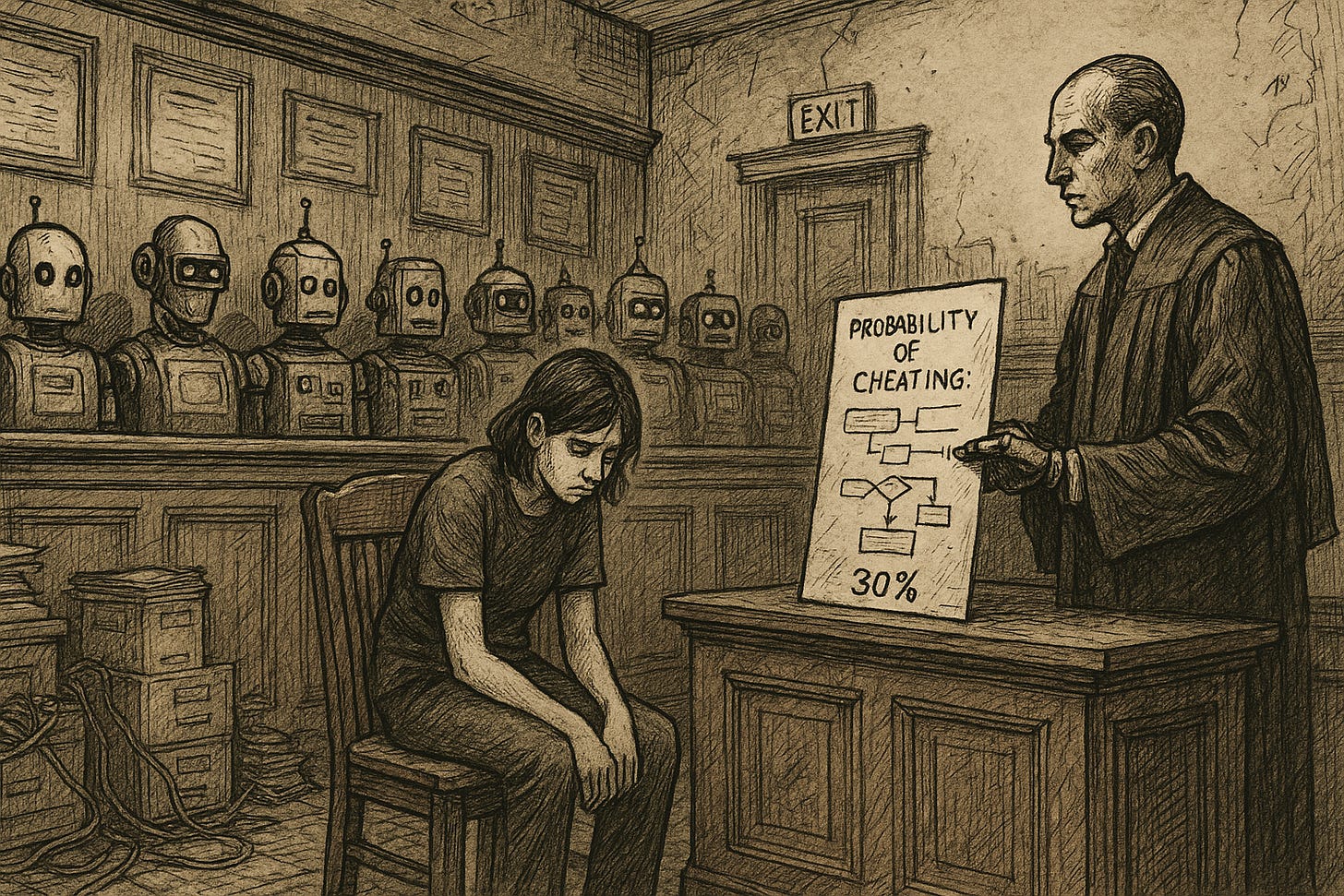

We also know false accusations are becoming part of the student experience, though rarely hear about the fallout up close:

Abeldt did have one bad experience, in which a professor accused her of using AI to write a discussion post in the form of a paper. The objective was to watch and analyze a mediation case on video, and write about it. The professor told her that an AI detector had flagged her piece for being about 30 percent AI written when, Abeldt said, she had not used any AI.

Rather than fight, she rewrote the paper, she said. She felt that her professor didn’t really understand what the detector was doing, such as picking up quotes she had cited from the video. To make sure she wasn’t flagged again, she turned phrases such as “she did an exceptional job of fulfilling her job as a mediator” to simpler wording like, “the mediator did a good job mediating.”

“I felt like I was having to dumb myself down,” she said. The experience confirmed her belief that many professors think students use AI only with bad intentions. She is on the pre-nursing track in college and imagines using AI in her future career. Health-care providers already use it, she noted, to make diagnoses and predict risks. A blended future, in which humans work alongside AI, doesn’t alarm her.

McMurtrie, Beth. “AI to the Rescue.” The Chronicle of Higher Education, 20 June 2025

It’s hard to imagine a more backward outcome. A student deliberately weakening their writing because of fear of being caught using AI. This isn’t an isolated case. Some students are now recording themselves writing papers, just in case they’re wrongly accused.

One of the best HS students I’ve taught in the past two years was falsely accused of using AI during her freshman year. She’s honest, meticulous, and took great pride in her work. The accusation shook her.

What message does it send when honest students are the ones being accused? Especially when they know dozens of others are cheating and getting away with it.

How long can students like this hold their trust in the system? How long before their frustration turns into resentment toward their peers, their professors, and the institutions that failed to protect them? How long before they decide that if no one else is playing fair, they might as well stop trying to?

And how are their parents, who pay massive tuition bills, supposed to react when they hear stories about false accusations, unchecked cheating, and no real accountability?

Grading For the Process Not the Product

This spring, I found myself quietly cheering every time I read a research paper that was clearly written by a real sophomore and not a machine.

How did I know? Because they were filled with grammatical mistakes, awkward sentences, confusing syntax, claims unsupported by evidence, and missing logic. What a strange moment to actually sigh in relief when reviewing work that you know is authentic because it was obviously created by a real, struggling writer rather than a pitch perfect synthetic algorithm.

Could these papers have been improved with AI? Absolutely.

But do we want better writing, or better writers?

I had redesigned the assignment so that 75% of the grade was based on process. Students had to document at least six research sessions. I warned them they’d hate it. The “research log” was harder than the final paper.

But they had to explain in detail what they did, which sources they found, how they found them, what information they used, and other details. These cumulative prompts weren’t AI-proof, but they were AI-resistant and proved well beyond their capacity to offload. Combined with individual student conferences, the result was clear: their papers reflected the actual work they put in.

Designing For Integrity

Everyone’s talking about how AI is changing education. But almost no one is asking what happens to the students still trying to learn the right way. How must they feel when the dominant story is “everyone is cheating their way through college”?

Even the students who have succumbed know that what they are doing with AI is cheating. But every college student right now also knows that AI is the future, that it is going to reshape employment, and it’s something they are going to have to be able to navigate.

So how do we design classrooms that hold both realities - that many students will use AI, but enough are also committed to learning without it?

One answer is to get back to basics. Teachers need to return to first principles: What are we trying to teach? What skills actually matter?

These are the real pedagogical questions. We need to ask them first without AI in mind. Then we need to ask them again, knowing AI is already here to stay. Where does it get in the way, and are there places where it could actually help?

The students who still want to learn, who can already see the long-term consequences of relying too heavily on AI, can’t keep doing it alone. If we don’t design for integrity, we’ll lose them to a system that makes cutting corners feel like the only rational choice.

Students who use AI to do all the work for them are screwed.

Students who avoid it at all costs are also screwed.

The TRICK is to find the very narrow path in between.

Respectfully, when you’re using a “tool” that exists through theft at scale, there is no acceptable use case for it. ChatGPT wouldn’t exist without the massive scraping of data without consent. Any use acts as a statement that declares, I’m okay with stealing from people.