This week, I finish a degree I started almost four years ago - a Master of Arts in the Liberal Arts from St. John’s College, home of the Great Books program which has seduced masochistic readers for decades. I enrolled online during the pandemic, juggling a full-time teaching load, family life, and texts that never stopped calling - Plato, Aristotle, Kant, Darwin. Several times a week over these past four years, I was planning my own classes and rushing to finish a section of The Iliad before a 10pm zoom, all while recent AI headlines blared in the background about the 'death of writing.' Now, between my 25th paper and final seminar, this time trying to parse Lobachevsky in real time, it hit me: The classrooms most resistant to AI aren’t the most innovative. They’re the ones that still demand something no machine can simulate: messy and collaborative human dialogue about deep and profound ideas. Just like Socrates did in the agora.

The Great Books are notoriously difficult. I’d tried Nietzsche on my own before, but without the pressure of discussion or the structure of a seminar, I’d always give up. The books were too dense, too slow, and too easy to put aside when real life got in the way.

I’d been assigned Plato in college and taught snippets of Hobbes, Locke and Adam Smith to high schoolers. But I’d never actually forced my way through Aristotle’s Physics or read carefully from Darwin’s Origin of Species, let alone tried to discuss them in detail at 11pm on a Tuesday across three time zones.

Now I understand why these books are more often name-dropped than read. They’re brutal. They ask for the kind of attention modern life no longer makes room for. And, when they’re the only assignment on the syllabus, they don’t care if you're tired, distracted, or burnt out. Show up to seminar without reading, and you might as well turn off your camera and go to sleep.

In our culture of digital distraction and hyper-efficiency - now turbocharged by AI - this kind of reading feels almost transgressive. Which is exactly why it matters.

Can a Chatbot Say Something New?

There’s an ongoing debate in AI circles about whether these models are - or ever will be - capable of generating truly original thought. Some claim they never can. Because LLMs aren’t human, they argue, by definition they can’t say anything meaningful about the human experience.

Others claim it's just a matter of time. That with enough data and compute, AI will eventually say something genuinely novel - maybe even as insightful about beauty, justice, or love as the ancients once were.

I’m not here to weigh in on that debate. At least not now.

What feels more urgent is celebrating what human thinkers have done for centuries. Throughout history and before electricity, the printing press, or formal education, they still managed to produce ideas that move us to this day. The density, clarity, and sheer audacity of what they wrote, often under candlelight, political threat, and the weight of illness or personal tragedy, remains nothing short of revolutionary.

Do we have anything written in the 21st century that will last like The Republic, The Divine Comedy, or Paradise Lost? Anything that future generations will be forced to reckon with, not because it’s assigned, but because it endures? I’m not so sure.

At St. John’s, we’re not taught about the Great Books. We wrestle with them directly. In seminar, there are no lectures or PowerPoints. No amusing John Green overviews, grade inflated projects or empty assignments. Just a dozen people in a room (or on Zoom), trying to unpack meaning through close reading and unpredictable discussion. Every class is different. Every insight can be a pleasant surprise or an unformed thought clicking into place. You always leave with more questions than answers.

And that carries over into the St. John’s writing philosophy.

The Last Paper AI Can’t Fake?

The papers assigned in the St. John’s program are an entirely different kind of animal. There’s no research, no outside sources, no “historical context.” Just you and the text. Quoting the book is fine as long as you say something interesting about it.

Could an AI write a St. John’s paper? Maybe. But it would miss the point entirely.

Students are given enormous freedom to explore what interests them. You’re forced to develop a thesis that often changes as you reread until the rhythm of the author’s language becomes second nature.

Over four years, I wrote more than twenty papers, and while every one was a different kind of intellectual challenge, they all had this in common: I was writing for myself and my own understanding and not to impress a teacher. No grades. Just thoughtful feedback.

My paper on Cicero’s De Oratore was one of the most rewarding things I’ve ever written. Not because it was brilliant, but because it was mine. When you generate your own question instead of just answering someone else’s, the investment is different. You care more. The result matters.

You don’t need to be in a graduate seminar to grapple with the ideas that make us human. If you select the right texts, these writers still speak to anyone willing to slow down and listen, including high school students.

Teaching While Being Taught

Teaching full-time while also being a student reminded me what my students are up against. Many are slogging through required courses or resume-padding electives, spending hours each night on homework that feels like drudgery. I realized how many assignments are more transactional than transformational. It gave me a sharper empathy for what school can do to curiosity.

We like to say students can’t read deeply anymore. But what would happen if we stopped drowning them in busywork and asked them to dive into something that actually mattered?

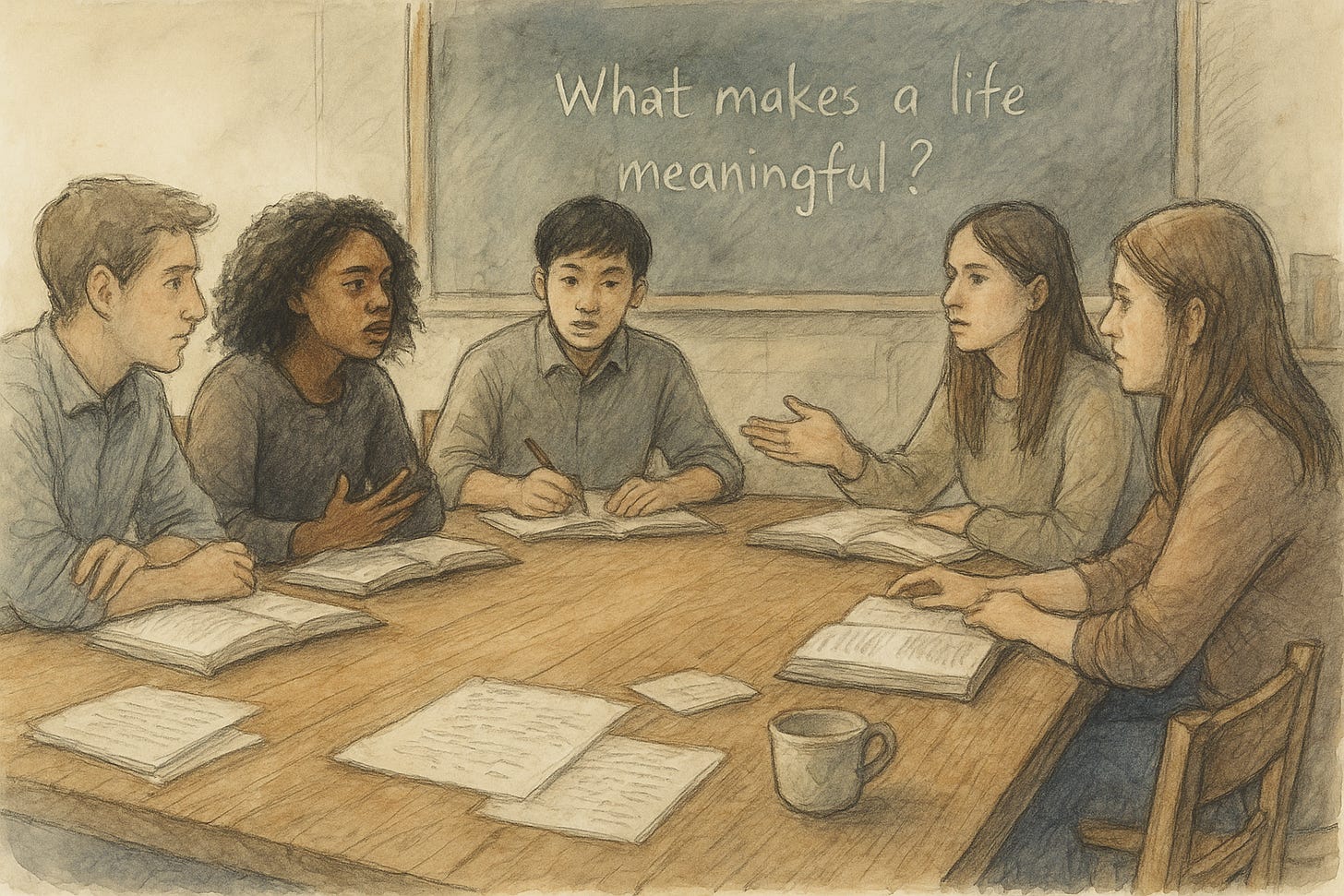

Inspired by the St. John’s program, I launched a Great Books elective at my school a few years ago. The inaugural class was a small group, but easily one of the most rewarding teaching experiences I’ve had in thirty years. We slowed down. We had real conversations about real questions. And the hunger for that kind of sustained attention was obvious.

Even in that class, I had to resist the temptation to assign quizzes for understanding, prepare study guides, or give mini-historical lectures. It wasn’t until later in the year that I saw how important it was not to crowd the course with distractions. The readings were the work. They were hard and deep enough to carry the weight on their own.

The ancients didn’t learn by filling out worksheets. They learned by arguing with each other, struggling with ideas, and, if they were lucky, reading the words of both their ancestors and contemporaries. That kind of learning can still work.

Maybe it’s a pipe dream to scale that kind of experience. But in the age of AI, I’m starting to think these are the kinds of classes that may matter most.

Final Thoughts

When I started the St. John’s graduate program four years ago, I used to joke that it was an intellectually indulgent degree, but not exactly practical. And maybe in a pre-2022 world, it wasn’t. It’s point isn’t career alignment or job optimization. The Great Books program has always been about something more essential. Just ask any of its graduates.

But with AI now automating so much routine work, and predictions of sweeping job disruption, I’m starting to wonder if the people trained to ask real, enduring questions - What is justice? What makes a life meaningful? How do we know what we know? - might actually be the ones best prepared for what’s coming.

The St. John’s style seminar may end up being the most AI-resistant educational experience we’ve got: real people, sitting around a table, unplugged, debating timeless questions along with some of the greatest minds that first asked them.

In a system obsessed with grades, scores, rankings, and metrics (many of them pedagogically dubious at best) this kind of learning may not look as impressive on a resume. But it cultivates something far rarer: the capacity to think deeply, listen closely, and stay with the hard questions that no machine can answer.

Excellent! I always regretted that I found out about St. John's too late -- I already had my degrees and was teaching full time and had a family. But I always regretted that I had missed it since I had the feeling that it would have been a perfect fit -- and this was decades before Zoom on online courses. Life has taken me other directions and I have no regrets about those but I loved reading about what you are doing and only wish that my kids or not my grandkids could have learned deeply with you.

Congrats on finishing!

I think about this a lot because we already have the foundation. Using AI for us allows us to learn more, produce more, and create more. But for newer generations, they don't have the foundational skills.